Summary

If the Strait of Hormuz were to close, the impact on the fertilizer complex could be severe. The nitrogen complex, and urea in particular, would bear the brunt, given the scale of the region’s importance to global exports (45% of all urea exports come from this region) and the interdependencies of other nutrients, such as MAP and DAP, which use ammonia for production. However, the potential impacts could run much deeper, hitting global sulfur and phosphate prices and further testing the cost structure of growers globally. We looked at a few scenarios, comparing the price impacts of partial and full closure across different time periods. Local markets would feel the impacts differently, but the consequences would be broad.

The Strait of Hormuz plays a key role in global fertilizer trade

In response to escalating Israeli and US military action against Iran in recent weeks, Iran has threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz, with Iranian media reporting over the weekend that the parliament had approved a measure to close the waterway. Final approval for such an action would depend on a decision from Iran’s top leadership.

However, there are many reasons why a closure of the Strait of Hormuz is unlikely. Still, the conflict between Israel and Iran has once again highlighted the important role that certain regions play in the global fertilizer complex. In late 2021 and into 2022, we saw how sensitive global fertilizer prices are to geopolitical events when natural gas prices in Europe spiked on the back of rising tensions and Russia invaded Ukraine.

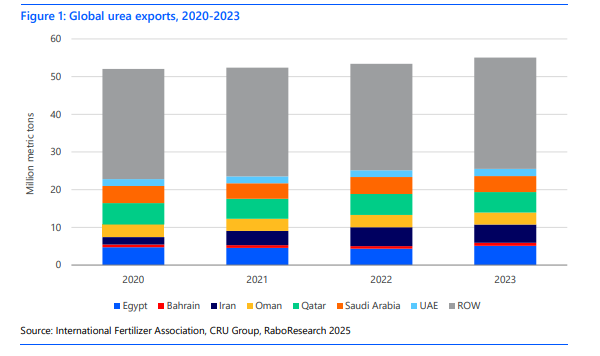

The Strait of Hormuz represents one of the most significant global fertilizer bottlenecks. Just 21 nautical miles at its narrowest point, the Strait of Hormuz could aptly be described as a nutrient highway. Not only does 20% to 30% of global seaborne oil pass through these waters, they are arguably the most significant bottleneck for global urea trade. Key urea exporters active in this trade route include Qatar (~5m mt/year), Iran (~5.5m mt/year), the UAE (~2m mt/year), Bahrain (~0.75m mt/year), and the east coast ports of Saudi Arabia (~2m mt/year). In close proximity but slightly beyond the strait lies the Omani port of Sohar, with Oman accounting for approximately 3m mt of global urea exports. Adding Omani volumes means that 30% to 35% of global urea exports are exposed to current tensions (not including west coast Saudi Arabian and North African volumes). Broaden this to Egypt – which is believed to have already seen production disruption from the most recent conflict between Israel and Iran – and the wider Middle East and the potential impact expands to roughly 45% of global urea exports (see figure 1).

The impacts will be seen most clearly in Brazil and India

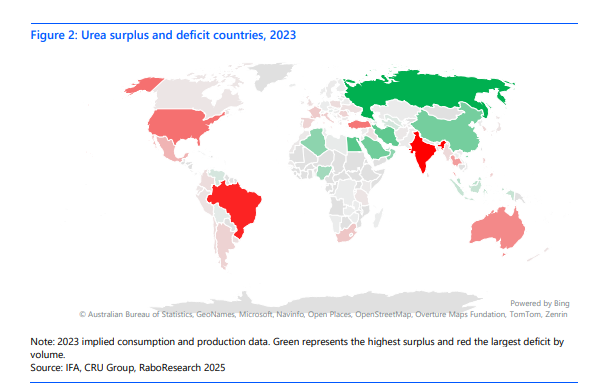

Primary impacts

While closure of the strait would certainly lift global fertilizer prices, the consequences on agriculture would hit different regions at different levels and different times. The seasonality of demand would dictate the timing of the impact (and agricultural severity), but the most exposed countries would undoubtedly be those that carry deficits. For urea, Brazil and India hold the largest deficits (see figure 2), with Brazil importing between 7.5m and 8.5m mt per year and India importing 7m to 11m mt per year, depending on the strength of government policy. Brazil has very little domestic fertilizer production, creating a broader macronutrient deficit, and it sits within a deficit region. Imports account for over 90% of Brazil’s urea demand and approximately 95% of its macronutrient demand, meaning that the consequences of price escalation are often most severe there.

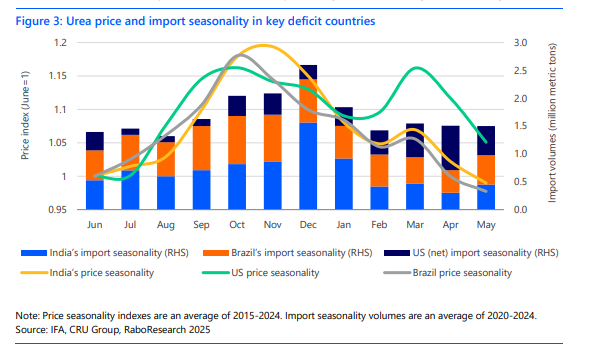

Seasonality of demand would also be a significant factor in local price formation. Any immediate risk of volatility would likely also point to Brazil, as import demand picks up seasonally from June through November, which aligns with pricing seasonality at the wholesale level. Compounding this risk is the fact that Brazil is behind schedule on its urea imports. When adjusted for seasonality, pricing in Brazil often peaks around October at the height of import demand for urea. If prices remain elevated for an extended period, this could pose a significant risk to the safrinha corn crop. The seasonal cadence of Brazil and India are largely matched, with peak demand and seasonal pricing often seen in December. In contrast, the US has two spikes, with the first and third quarter of the calendar year showing higher seasonal pricing, with a greater share of demand met by imports in Q1 (see figure 3). In essence, the immediate price and volume risks point to Brazil, followed by India, with seasonality offering some risk mitigation for US growers.

The European Union has recently imposed new import tariffs to reduce its reliance on fertilizers from Russia and Belarus, creating a need to source around 1m mt from alternative suppliers. North Africa and the Middle East are the most likely options, though both regions face rising geopolitical tensions. Over 25% of the EU’s nitrogen fertilizer imports already come from Egypt, whose urea capacity is currently shut down due to cuts in gas supplies from Israel. With the fertilizer offseason approaching, there is a short window for logistical adjustments. However, if regional instability worsens, importers may face sharply higher prices, regardless of origin. EU producers could scale up output but likely at higher energy costs, as conflicts also affect oil and gas markets. These pressures add to increased Russian tariffs and the upcoming costs from the EU Emissions Trading System and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, set to begin in 2026 and 2027. The result: higher production costs for European farmers in the next crop season.

Another primary impact, which is already poised to affect global fertilizer supply, is the halting of Egyptian and Iranian urea production as a consequence of the escalation of the Israel-Iran conflict.

Secondary impacts

Although urea has the most visceral risk exposure to the Strait of Hormuz, phosphates and sulfur are integral direct nutrients for growers. Roughly 50% of global sulfur production is used to produce sulfuric acid, and as much as 80% of sulfuric acid is used in the production of phosphate fertilizers. Phosphate prices have been stubbornly high of late, due to quotas limiting China’s activity in the export market, high rock prices, and high sulfur prices constraining the complex. Saudi Arabia has been increasing its relevance as a global phosphate supplier, ratcheting up its exports by roughly 4m mt per year over the last five years at a time when Moroccan (rock) and Chinese finished volumes have been less plentiful. This has impacted trade flows and created greater dependencies on certain countries. As countervailing duties have changed the trade flow of phosphate fertilizers to and from the US, Saudi Arabia has seen its market share of US MAP imports nearly triple, from ~10% up to 30%, and its market share of US DAP imports more than double, from 20% up to 50%.

The supply of sulfur out of the Persian Gulf and the part that this byproduct plays as an intermediate in global phosphate production add to the potential impacts of a closure. The combined exports of elemental sulfur from Iran, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia exceeded 8m mt in 2024, representing a significant percentage of the estimated 20m to 25m mt of annual global elemental sulfur exports. The diversity of sulfur supply is greater than the diversity of sulfuric acid supply – which would be the ultimate choke point here – but any impacts on the trade of sulfur out of the Persian Gulf would directly affect the broader phosphate complex. The breadth of the impact on phosphate production would span from Asia to North Africa.

Tertiary impacts and reactions

Tertiary impacts are harder to qualify. However, we could break them down into two buckets: market-led impacts and government-led impacts, with an overreaching theme of a ”beggar thy neighbor” strategy across both buckets. Even without the immediate impact of a trade disruption, a wartime premium could be baked in to global prices through higher freight and insurance costs. Additionally, any sense that a closure is forthcoming could precipitate early or offseason purchases, further compounding any price volatility and kicking into motion other actions. The relationship between energy prices and the underlying price of fertilizers is key and needs monitoring. The spread between regional energy prices and local fertilizer prices could render production for some unaffordable. This dynamic played out in Europe, despite soaring nitrogen prices, leading to a 70% curtailment of ammonia production in 2021/22 that only compounded the issue. The relationship between agri commodity prices and fertilizer prices is also connected to that. China’s commitment to export urea in the offseason could well be tested by rapidly rising domestic urea prices. Similarly, mechanisms appear to be baked in to European tariffs on Russian fertilizer that could water them down if affordability for growers were tested.

Beyond this, we could also start to see some structural changes in trade and efforts to secure more consistent volumes through bilateral agreements. Scarcity regions may pursue agreements with suppliers. These kinds of relationships could occur, for example, between India, looking to secure phosphates, and Morocco. Similarly, Brazil may look to guarantee its supply of phosphates, nitrogen, and potash from the likes of Morocco, as well as the former Soviet Union. In the case of Brazil, this would be an irregular move and a break from more traditional free-market values, but it would align with political constituencies, agriculture’s importance to Brazil, and the geopolitical middle ground that the country occupies. A greater number of bilateral relationships would narrow the market for fertilizer trade, which would bring its own implications for pricing and traders. Alternatively, bilateral offtake agreements with or investments in low-cost, politically stable environments like the US could precipitate investment and the acquisition of exports.

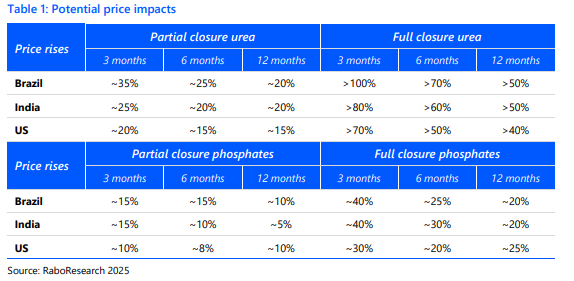

Immediate closure would increase prices worldwide

To paraphrase a Nobel Prize winner, “All models are wrong, some are helpful.” The forecasts in table 1, below, assume an immediate closure (mid-June), meaning the seasonal impact is more significant in Brazil. The recent example of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the impacts seen in 2021 and 2022 provides a useful precedent. In that price example – which was a mixture of war premium, impacted supply, and perceived impact on supply – we saw a virtual doubling in price relative to today’s fertilizer price index. By comparison, some of our forecasts may seem quite conservative. But ostensibly, the riskiest time frame is the immediate future, with a full closure worse than a partial closure. As we saw in the example of Belarusian potash, the longer the time frame, the greater the capacity to create mitigating logistical factors. In the particular case of a closure of the Strait of Hormuz, the logistical mitigants may be less viable than Belarus railing potash across Russia.

Higher pricing may incentivize marginal capacity to ramp up production and farmers to adjust farming practices to tamp demand. Other factors like Indian nutrient subsidies could similarly come into play, impacting demand across a longer time horizon. And, for some regions, affordability, finance, and liquidity may limit demand in the near term. Phosphates are broadly seen as having less price risk to the upside, chiefly because of their current elevated prices. Our recent fertilizer publication highlighted the potential for affordability issues to lead to demand destruction, but the impacts of the conflict lift affordability risks to a much higher level.

Authors

Samuel Taylor

Senior Analyst – Farm Inputs

samuel.taylor@rabobank.com

Bruno Fonseca

Senior Analyst – Farm Inputs

bruno.fonseca@rabobank.com

Doriana Milenkova

Analyst – Farm Inputs

doriana.milenkova@rabobank.com

Disclaimer

Disclaimer

This publication is issued by Coöperatieve Rabobank U.A., registered in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and/or any one or more of its affiliates and related bodies corporate (jointly and individually: “Rabobank”). Coöperatieve Rabobank U.A. is authorised and regulated by De Nederlandsche Bank and the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets. Rabobank London Branch is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority (“PRA”) and subject to regulation by the Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the PRA. Details about the extent of our regulation by the PRA are available from us on request. Registered in England and Wales No. BR002630. An overview of all locations from where Rabobank issues research publications and the (other) relevant local regulators can be found here: https://www.rabobank.com/knowledge/raboresearch-locations

The information and opinions contained in this document are indicative and for discussion purposes only. No rights may be derived from any transactions described and/or commercial ideas contained in this document. This document is for information purposes only and is not, and should not be construed as, an offer, invitation or recommendation. This document shall not form the basis of, or cannot be relied upon in connection with, any contract or commitment by Rabobank to enter into any agreement or transaction. The contents of this publication are general in nature and do not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. The information in this document is not intended, and should not be understood, as an advice (including, without limitation, an advice within the meaning of article 1:1 and article 4:23 of the Dutch Financial Supervision Act). You should consider the appropriateness of the information and statements having regard to your specific circumstances and obtain financial, legal and/or tax advice as appropriate. This document is based on public information. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness.

The information and statements herein are made in good faith and are only valid as at the date of publication of this document or marketing communication. Any opinions, forecasts or estimates herein constitute a judgement of Rabobank as at the date of this document, and there can be no assurance that future results or events will be consistent with any such opinions, forecasts or estimates. All opinions expressed in this document are subject to change without notice. To the extent permitted by law Rabobank does not accept any liability whatsoever for any loss or damage howsoever arising from any use of this document or its contents or otherwise arising in connection therewith.

This document may not be reproduced, distributed or published, in whole or in part, for any purpose, except with the prior written consent of Rabobank. The distribution of this document may be restricted by law in certain jurisdictions and recipients of this document should inform themselves about, and observe any such restrictions.

A summary of the methodologies used by Rabobank can be found on our website.

Coöperatieve Rabobank U.A., Croeselaan 18, 3521 CB Utrecht, The Netherlands. All rights reserved.

© 2025Tertiary impacts are harder to qualify. However, we could break them down into two buckets:

market-led impacts and government-led impacts, with an overreaching theme of a ”beggar thy

neighbor” strategy across both buckets. Even without the immediate impact of a trade disruption,

a wartime premium could be baked in to global prices through higher freight and insurance costs.

Additionally, any sense that a closure is forthcoming could precipitate early or offseason

purchases, further compounding any price volatility and kicking into motion other actions. The

relationship between energy prices and the underlying price of fertilizers is key and needs

monitoring. The spread between regional energy prices and local fertilizer prices could render

production for some unaffordable. This dynamic played out in Europe, despite soaring nitrogen

prices, leading to a 70% curtailment of ammonia production in 2021/22 that only compounded

the issue. The relationship between agri commodity prices and fertilizer prices is also connected

to that. China’s commitment to export urea in the offseason could well be tested by rapidly rising

5/6 RaboResearch | What a closure of the Strait of Hormuz could mean for global fertilizers | 24 June 2025

Please note the disclaimer at the end of this document

domestic urea prices. Similarly, mechanisms appear to be baked in to European tariffs on Russian

fertilizer that could water them down if affordability for growers were tested.