Summary

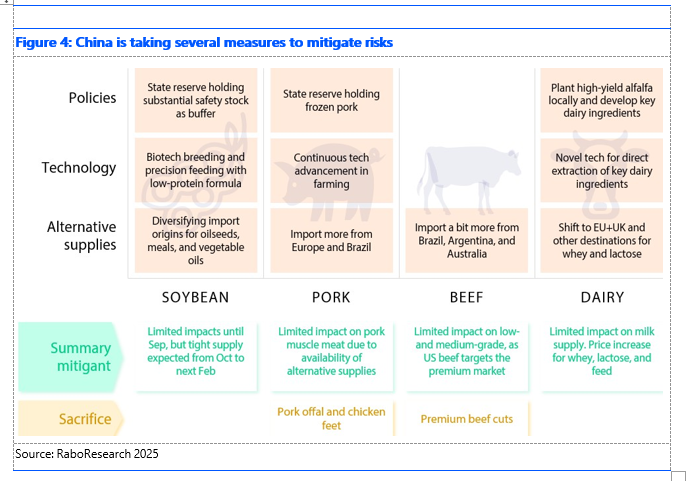

US President Trump’s trade war will have limited impact on China’s food security. China’s food staples market will more than stay afloat without the support of US farmers. Although China’s animal protein industries are exposed to President Trump’s tariffs via their dependence on imported feed crops, they can source more from other countries, rely on safety stocks from state reserves, and adjust feed rations to lower the use of imported feed crops accordingly.

However, discretionary spending on high-value-added food might be negatively impacted by this ensuing trade war. If China’s economy is negatively impacted by the slowdown of the global economy, China’s consumers might be less inclined to buy these products. But this impact would be mostly indirect, as the US holds only a small share of China’s imports.

Executive Summary

The trade war initiated by US President Trump puts a spotlight on the food and agribusiness (F&A) trading relationship between the US and China. In this report, we describe the worst-case scenario – that is, an absolute decoupling of the relationship – from China’s perspective. We conclude that a de facto embargo on trade between the US and China would only have limited impact on China’s food economy.

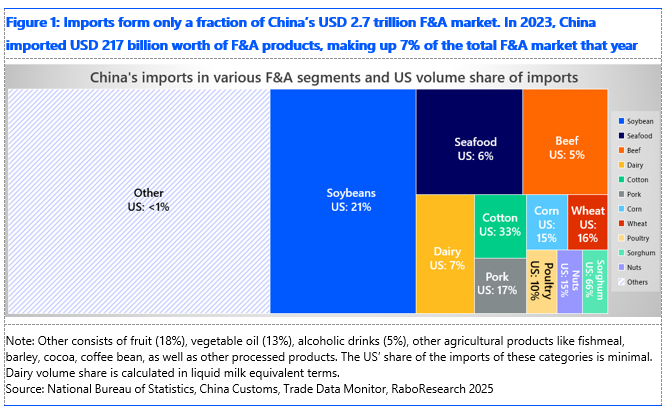

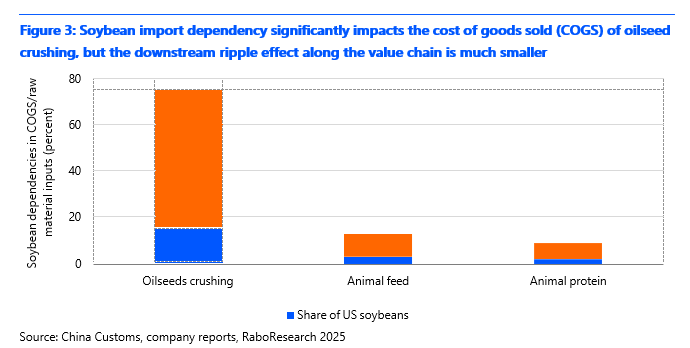

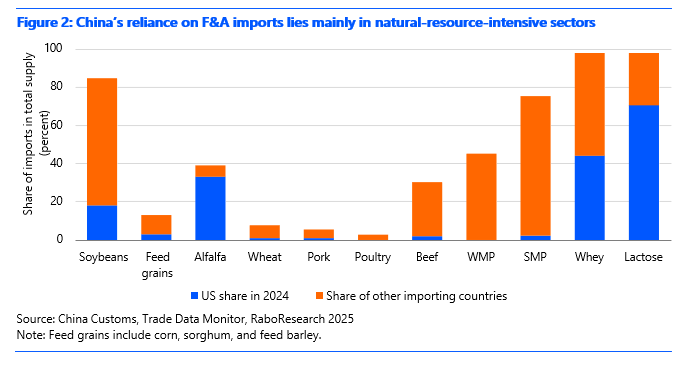

Imports make up 7% of China’s food economy, but import dependency varies widely across products, as do the reasons why China imports these food products. Because agricultural land is scarce in China, the import of land-intensive, low-value-added feed crops like soybeans and alfalfa is necessary. This reliance on feed crop imports, though, ensures self-sufficiency in other land-intensive food grains like wheat and rice, which are of higher strategic importance.

China benefits from oversupply of coproducts in the global meat industries, such as offal meat and chicken feet, products valued by Chinese consumers but not so much by the rest of the world. Imports of these products keep a lid on domestic prices of offal meat and chicken feet. This is also why China imports animal protein when domestic supply shocks occur. For example, when China combated a severe outbreak of swine fever, the increased import of pork kept domestic pork price increases in check.

Another driver of China’s food imports is the country’s growing discretionary spending on more indulgent food items like cocoa, avocados, durians, and coffee. This is also true for branded consumer food and beverage products linked to their place of origin, such as whiskey, wine, high- quality beef, premium seafood, and certain cheeses.

US President Trump’s trade war will have limited impact on China’s food security. China’s food staples market will more than stay afloat without the support of US farmers. Although China’s animal protein industries are exposed to President Trump’s tariffs via their dependence on imported feed crops, they can source more from other countries, rely on safety stocks from state reserves, and adjust feed rations to lower the use of imported feed crops accordingly.

However, discretionary spending on higher-value-added food might be negatively impacted by this ensuing trade war. When China’s economy is negatively impacted by the slowdown of the global economy, China’s consumers might be less willing to buy these products. But this impact is mostly indirect, as the US only holds a small share of China’s imports.

The impact of the trade war on China’s food economy must ultimately be absorbed by China’s consumers in the form of higher food prices. This will happen either indirectly, when the impact runs through China’s industries and each segment bears increased costs that are ultimately passed on to consumers, or directly, when imports that are consumed without further domestic processing become costlier.

Grains & Oilseeds

China will proactively diversify its G&O import origins to compensate for the loss of US supplies

In 2024, China imported approximately USD 15 billion worth of grains and oilseeds from the US, making G&O the leading category in trade between the two countries. According to 2024 trade data, the major agricultural commodity imports from the US to China included wheat (16% of China’s total wheat imports), corn (15% of total corn imports), sorghum (66% of total sorghum imports), and soybeans (21% of total soybean imports). However, with significant tariffs levied on these imports, trading volumes are expected to drop to zero until trade negotiations resume.

- For wheat, China will diversify its imports to other suppliers such as Australia, Canada, France, Kazakhstan, and China is fairly self-sufficient in common wheat, which contains medium gluten levels. However, for high-gluten wheat used in high-end bakery products, China faces a structural deficit. Without access to US hard wheat, China will need to source more Canada Western Red Spring wheat and Australian hard wheat.

- Both imported corn and sorghum are used as feed grains. With US corn imports expected to halt, China will turn to alternatives such as Brazilian corn, Australian feed barley, Ukrainian corn, Argentine sorghum, and French feed barley.

- RaboResearch does not anticipate significant supply concerns for imported food and feed grains, but the main concern lies with soybeans. A bumper harvest of Brazilian soybeans will ensure sufficient supplies to meet Chinese demand until the end of Q3 2025. From October 2025 to February 2026, however, a continuation of the trade war could see China facing some shortage concerns if Brazil runs out of old crop stock before new crops are available. China would need to pay premiums to import more soybeans from Argentina and Uruguay, and direct imports of Argentine soymeal could also be an option. China would also need to release state reserves to supplement supply.

The US will reduce imports of used cooking oil from China and shift to domestic US soybean oil

The US does not import many Chinese G&O products. Nevertheless, the US imported approximately USD 1.3 million metric tons of used cooking oil (UCO) from China in 2024, worth roughly USD 1.1 billion. Due to the significant tariffs imposed, including both the 125% reciprocal tariff and the 20% “fentanyl” tariff, trading volumes are expected to drop to zero until trade negotiations resume. This will increase the use of alternative oils and fats, particularly in the biofuel sector, with US domestically crushed soybean oil emerging as the primary beneficiary.

Farm Inputs

China is expected to redirect its vegetable seed imports from the US to Europe and Japan

China does not import many US farm input products, except for vegetable seeds. In 2024, China imported approximately USD 480 million worth of vegetable seeds from the US, accounting for 22% of its total imports. These included cabbage seeds, carrot seeds, tomato seeds, lettuce seeds, onion seeds, and more. We expect that these could be replaced by seeds imported from Europe and Japan, as well as domestic seeds.

The US heavily relies on Chinese agrochemical imports, and US farmers will face higher costs due to tariffs, despite some exemptions

The US relies on Chinese imports for many essential agrochemical active ingredients and intermediates. The trade value of such imports was estimated at USD 2 to 3 billion in 2024, including both active ingredients and formulated pesticides. The White House has included some agrochemical active ingredients – including glyphosate, glufosinate, paraquat, and diquat – in the exemption list for the 125% reciprocal tariff, but the 20% tariff related to fentanyl issues still applies. Nevertheless, the overall high tariffs are expected to cause a substantial decline in export volumes if a trade agreement fails to materialize. The impact of these tariffs on individual Chinese agrochemical companies will depend on their product mix and export exposure to the US market.

Animal Protein

China’s pork market to face tariff impact, with pork offal hit hard

With the cumulative tariffs, China’s import tariffs on US animal proteins range from 150% to 180% at the time of writing. This makes direct trade impossible. The US is not a big supplier of pork meat to the Chinese market, but it is the largest supplier of pork offal to China. In 2024, the US accounted for 6% of China’s total pork meat imports, but a whopping 27% of China’s pork offal imports. China was the third-largest destination for US pork and pork product exports in 2024, accounting for 13% of total US exports. The retaliatory tariff on US pork will have relatively limited impact on China’s pork muscle meat market and may even benefit local Chinese pork companies who might otherwise face oversupply issues. But there will be an impact on China’s pork offal supply, and we observe three possible scenarios:

- China reduces imports of pork offal meat, leading to higher prices in the Chinese market.

- Smuggling will increase, as the US will increase exports to Vietnam and Hong Kong, which will be reshipped to mainland China via grey channels.

- China will increase imports from other countries (mainly European countries and Brazil) and approve more exporting plants to replace US exports.

The reduction in US whey imports (and soybean, likely starting in Q4 2025) will likely raise the cost of pork production – particularly the cost of piglets, as whey is mainly used in piglet feed. These proteins can be substituted by amino acids, but some are very expensive and would raise costs as well. Large-scale feed/pig players are in a better position to innovate feed formulas to manage the cost increase.

Beef market impact limited due to 4.8% US share

China is the world’s largest beef importer, with 2.87 million metric tons worth of import volume in 2024. US beef made up only 4.8% of China’s total imports in 2024, which dropped significantly in recent years, primarily due to the high prices of US beef as opposed to low local prices. But for the US, China holds a more important position, as it remains the third-largest destination for US beef exports, accounting for 15% of total US export value in 2024. In 2025, US beef supply has been relatively tight, lowering the amount available for export to China, regardless of tariff rates. China’s retaliatory tariff on US beef will have a limited impact on Chinese supply. China will import more from other countries, such as Brazil and Australia, to fill the gap. The Brazilian agriculture minister has already indicated that China will likely approve more Brazilian beef plants soon.

Poultry market largely unaffected, but chicken feet to see impact

Before the tariff war, China’s imports of poultry from the US had already fallen significantly in recent years, mainly due to local production growth and the high prices of US chicken. China remains the third-largest destination for US chicken, although its share of total US exports fell from 18% in 2022 to just 8.8% in 2024. US chicken forms only 6% of China’s total imports, but 10% of China’s chicken feet imports originate in the US. So, the high tariffs will mainly impact chicken feet supply in China. We expect chicken feet prices to go up temporarily, but since this is more of a snack than a staple food in the Chinese diet, the impact on the main market will be limited.

For all the animal protein species, global trade patterns will shift. The US will export more pork, beef, and poultry to other countries, while direct shipments to mainland China will stop for now. China will import more from other existing suppliers: Brazil and the EU for pork, Brazil and Australia for beef, and Brazil, Thailand, and Russia for poultry. Animal protein product prices in China will likely go up, but this will be a modest increase. Mild inflation aligns with the short-term goals of the Chinese government, which aims to increase retail prices to support the profitability of the supply chain and to stimulate consumption.

Seafood market becomes volatile as China halts exports to the US

China is the largest seafood exporter and a key importer in the world. The US contributes 6% to China’s total seafood imports, while 11% of China’s total exports goes to the US. Although China may find alternative suppliers to replace US seafood imports, tariffs will cause a significant impact on export-oriented species in China. Tilapia is the key product China exports to the US. With the exporting business halted for the time being, a surplus of tilapia will flood the local market at low prices, putting pressure on sales of other types of seafood. Aquaculture in China will face lower demand, price reduction, and extra costs as it adjusts operations to local needs. This will also impact aquafeed players, whose profits will be squeezed by lower farming interest until the supply chain adapts to these changes.

Dairy

China has reduced its reliance on imported dairy products

China has reduced its reliance on imports of dairy products and commodities, as the country has increased its domestic milk supply from 31 million metric tons in 2018 to 40.8 million metric tons in 2024. This marks a significant increase in China’s milk supply self-sufficiency, from 70% to 85%. However, China still needs to import some dairy products, and Oceania is the largest import origin for cheese (74% of total imports), butter (86%), whole milk powder (WMP) (96%), and skim milk powder (SMP) (81%).

Retaliatory tariffs will mainly impact imports of US whey and lactose

The US is not a major import origin for dairy commodities, and China’s exposure to US exports is mainly in whey, lactose, and alfalfa. China’s retaliatory tariffs mainly impact the following imported categories: whey, whey protein concentrates and whey protein isolate (WPC80/WPI), lactose, alfalfa hay, and other forage.

In 2024, China imported 661,000 metric tons of whey, and the US accounted for 45% of China’s imports, followed by the EU+UK at 35%. Large volumes of the low-protein whey imported are for piglet feed.

From 2018 to 2019, China’s whey imports declined from 557,000 metric tons to 453,000 metric tons. US import volumes declined from 47% to 35%. The EU+UK gained 7% import share from 2018 to 2019, accounting for 45% of the import volume share in 2019.

In 2024, China imported 39,646 metric tons of high-protein whey (WPC80/WPI), with the EU+UK as its largest trading partner (39%), followed by the US (34%) and Oceania (25.5%).

China is by far the world’s largest lactose importer. In 2024, imports totaled 152,000 metric tons. Of this total, the US and the EU+UK represented 72% and 22.6%, respectively. Oceania accounted for 5% of total imports.

China will increase imports from alternative destinations, benefiting the EU, the UK, South America, and Oceania

We expect retaliatory tariffs to have an impact on the whey market. China will increase imports from other countries, shifting to the EU and the UK to source whey (provided the trade tensions of

China’s probe into EU dairy subsidies do not escalate), South American countries like Argentina for low-protein whey, and the EU, the UK, and Oceania for high-protein whey and lactose.

Increased costs will be absorbed throughout the value chain

We expect the increased costs of the impacted categories will be absorbed throughout the value chain, with lower margins likely for traders (like in 2018/19 when both US exporters and Chinese importers absorbed part of the tariff costs). The increased costs are likely to impact Chinese end- users in the animal and human nutrition sector. Depending on the value of the brand power and consumer sentiment on spending, the increased cost may need to be absorbed by Chinese end- users (e.g., sports nutrition/weight-management manufacturers, low-protein whey for piglet feed, lactose for animal feed, bakery, confectionary, infant and adult nutrition) and/or be passed on to consumers.

Chinese dairy players will accelerate plans to develop dairy ingredients to secure supply

Leading Chinese dairy players are exploring the possibility of locally manufacturing higher-value- added dairy ingredients, but uncertainty lies in technological breakthroughs and the cost of investment. Some representatives call for establishing special financial subsidies to support enterprises aiming to overcome technological barriers and improve the regulatory system to evaluate new technologies and processes for key ingredients.

The dairy sector will focus on upgrading from primary low-value-added to higher-value-added processing to unleash long-term dairy consumption potential. Potential steps include increasing domestic substitution of key dairy ingredients like whey, achieving technological breakthroughs in producing ingredients, reducing the cost of production/manufacturing, and providing financial subsidies for new technologies and processes of key dairy ingredients.

Domestic substitution and formula adjustment will help to mitigate increasing costs of feed and feed ingredients

China has been increasing its supply of high-quality forage. Dairy cows in China are commonly fed three types of rations: forage grass/alfalfa, concentrated feed, and supplementary feed. The costs of feed and feed ingredients will rise in Q4 2025, especially those with high import dependency on the US, if trade tensions continue.

In 2024, China imported 1.3 million metric tons of alfalfa hay and other forage, with the US, Australia, and Spain accounting for 70%, 17%, and 6.8%, respectively. Of this, 1.1 million metric tons was alfalfa hay, with the US representing 85% of total import volumes. As with whey and lactose, we expect China to increase imports of alfalfa hay from other countries like Spain.

However, given the US’ dominant position in alfalfa imports, part of the increased costs will have to be passed on to dairy farming operators that strongly rely on US imports of alfalfa hay. After the implementation of tariffs, domestic substitution of alfalfa hay volumes will increase. China’s dairy farms will reduce their reliance on imported alfalfa, with the government having developed several high-yielding alfalfa farms in the Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Ningxia provinces to increase the domestic supply. Lactose will experience a similar trend in animal feed. We expect prices of lactose to increase, which will drive up the cost of lactose usage in animal feed. Consequently, part of the costs will be passed on to end-users. In the meantime, dairy farms will also adjust their feed formula to maximize cost efficiency and nutrition.

Beverages and Consumer Foods

China sees net exports for baijiu and net imports for other alcoholic drinks, but trade war impact is minimal

The top players in beer – including CRB, Tsingtao, AB InBev, Yanjing, and Carlsberg – which accounted for over 75% of market share in 2023 (per Euromonitor), mainly produce and sell in China. On the cost side, 80% of the industry’s use of barley is imported, mainly from Australia, Canada, France, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Russia, and Argentina. Different companies might have different mixes of barley source countries.

China’s exports of beer account for about 2% of domestic production volumes, and the US accounts for a small percentage of China’s beer exports. China’s beer imports come mainly from Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain, and total imports represent about 1% of domestic consumption. Therefore, the imports and exports of beer seem minimal compared to domestic consumption. On the other hand, it is important to consider the tariff impact on China’s beer companies’ imports of barley, which they source mainly from Australia, France, and Canada.

The leading players of baijiu are all Chinese companies that produce and sell in China with steady local supply chains. China’s exports of baijiu products account for 0.2% of total baijiu production volumes in China. We estimate that the US accounts for 6% to 7% of this export volume.

China is an important producer and consumer of wine. But exports represent only a small part of sales for most domestic wine producers. China mainly exports wine to Hong Kong, North Korea, Singapore, France, Myanmar, Australia, Macau, Russia, Italy, and Japan. For overseas producers, China is a strategic market. Its import volumes of wine are about 80 times that of its export volumes and are sourced mainly from France, Chile, Italy, Spain, the US, New Zealand, Germany, South Africa, Argentina, and Georgia.

Brandy and whiskey accounted for 35% and 26% of China’s import volumes of liquor in 2023. France supplied over 95% of China’s imported brandy. The UK accounted for over 85% of China’s imported whiskey. The US, Japan, and Ireland, combined, accounted for only 10% of China’s imported whiskey.

On the cost side, across beverage categories, glass bottles exported to the US are under anti- dumping investigation.

The trade of soft drinks between China and the US represents a small fraction of China’s total trade in the category

In general, both imports and exports of soft drinks remain insignificant compared to domestic consumption. China exports soft drinks to Hong Kong, the US, South Korea, Myanmar, and others. We estimate the US accounted for about 7% of China’s exports of soft drinks in 2024. On the other hand, about 10% of China’s imported soft drinks come from the US.

On the cost side, China is one the world’s most important exporting countries of sweetener (e.g., saccharin, sodium cyclamate, stevia, sucralose, and aspartame) and is particularly important in the production of erythritol. But in general, the US accounts for less than 10% China’s total exports of sweeteners. In addition, China might contribute about 9% to 10% of US tea leaf imports, according to the China Association for the Promotion of International Agricultural Cooperation.

Domestic players dominate China’s staple food market, whose overseas expansion might be affected

The trade war’s overall impact on China’s staple food market should be limited. For staple foods like instant noodles, the market is dominated by domestic players who produce and sell mainly domestically. These players are also seeking overseas expansion opportunities, but the contribution of foreign sales to the revenues of their respective companies should remain minimal at this stage. There might also be some imports of instant noodle products from South Korea and Japan, but these account for only a small portion of total consumption.

International brands play an important role in China’s snack food market, but the supply chain is mostly localized

For snack foods, the top players are international names such as Mars, Mondelēz International, and PepsiCo, whose aggregate share in China’s snack food market is about 11%, according to Euromonitor. Nevertheless, over 90% of their supply chain is localized. There are also direct imports of snack foods. For example, imports might account for 10% of chocolate confectionery and 5% of sugar confectionery in China. Out of these imports, the US share is very small (e.g., about 5% of imported chocolate). In terms of channels, warehouse retailers such as Sam’s Club and Costco often see higher sales of imported products than other retailers do, except for the most affected cross-border e-commerce. They, therefore, might be affected in the short term, but we expect them to further localize their supply chains and mitigate the impact. As China’s snack market is quite fragmented with diversified consumer demand, we believe the overall impact should be limited, but the market could see a gradual shift in brand/product mix.

On the cost side, China’s consumer food companies might import raw materials such as cocoa and sugar from Brazil, nuts from Australia and the US, as well as packaging materials. First of all, the US should account for only a small portion of China’s raw material imports. And if there is any impact to be felt, we expect this will come in the form of a shift toward other source countries. Secondly, while there is not much direct impact, we believe the prevailing trade war might lead to increased international logistics service costs (and even some price volatility in domestic logistics service) and lengthened transportation time, potentially pressuring the margins of consumer food companies.

Chinese foodservice suppliers might need to secure local supply chains to pursue their overseas expansion goals

Many Chinese foodservice brands have been exploring overseas expansion in recent years. These foodservice providers have proactively secured local supply chains for their business expansion, so the impact of the trade war should be limited.

Authors

|

Dirk Jan Kennes

|

Head of RaboResearch F&A Asia

|

Dirk.Jan.Kennes@rabobank.com

+852 21032430 |

|

Lief Chiang

|

Senior Analyst – Grains & Oilseeds,Farm Inputs

|

Lief.Chiang@rabobank.com

+86 21 28934670 |

|

Pan Chenjun

|

Senior Analyst – Animal Protein

|

Chenjun.Pan@rabobank.com

+852 21032430 |

|

Michelle Huang

|

Senior Analyst – Dairy

|

Michelle.Huang@rabobank.com

+86 21 28934677 |

|

Rena Ma

|

Research Analyst – ConsumerFoods and Beverages

|

Rena.Ma@rabobank.com

+852 21032431 |

Disclaimer

This document is meant exclusively for you and does not carry any right of publication or disclosure other than to Coöperatieve Rabobank U.A. (“Rabobank”), registered in Amsterdam. Neither this document nor any of its contents may be distributed, reproduced, or used for any other purpose without the prior written consent of Rabobank. The information in this document reflects prevailing market conditions and our judgement as of this date, all of which may be subject to change. This document is based on public information. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or derived from sources believed to be reliable; however, Rabobank does not guarantee the correctness or completeness of this document, and does not accept any liability in this respect. The information and opinions contained in this document are indicative and for discussion purposes only. No rights may be derived from any potential offers, transactions, commercial ideas, et cetera contained in this document. This document does not constitute an offer, invitation, or recommendation.

This document shall not form the basis of, or cannot be relied upon in connection with, any contract or commitment whatsoever. The information in this document is not intended, and may not be understood, as an advice (including, without limitation, an advice within the meaning of article 1:1 and article 4:23 of the Dutch Financial Supervision Act). This document is governed by Dutch law. The competent court in Amsterdam, the Netherlands has exclusive jurisdiction to settle any dispute which may arise out of, or in connection with, this document and/or any discussions or negotiations based on it. This report has been published in line with

Rabobank’s long-term commitment to international food and agribusiness. It is one of a series of publications undertaken by the global department of RaboResearch Food & Agribusiness.

© 2025 – All rights reserved